On November 7, 2024, the FDA announced that it is proposing to remove oral phenylephrine as a drug that is permitted for use in over-the-counter (OTC) drug products. This is a good decision for consumers, because phenylephrine is ineffective as an ingredient, and should never have been authorized as a cold remedy.

In today’s post I want to review the long path to reconsider the FDA’s approval phenylephrine, and I will quote extensively from some of my past posts.

Colds are ubiquitous. Surprisingly, while there are literally dozens of cough and cold remedies on pharmacy shelves, they all use combinations of the same core handful of ingredients. And the evidence supporting some of these products is very, very weak.

In 1976, the FDA concluded that three medicines were safe and effective for the treatment of nasal congestion caused by colds, allergies, and sinusitis: phenylpropanolamine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylephrine. Almost 25 years later, phenylpropanolamine was withdrawn from the market after use was associated with strokes. Pseudoephedrine is an effective decongestant that is chemically very similar to methamphetamine, a addictive and controlled drug that is subject to abuse. Pseudoephedrine does not share the same stimulant properties as methamphetamine, though it can cause jitteriness, mild tremors, and insomnia. However, because pseudoephedrine can be used to manufacture methamphetamine, the over-the-counter sale of cough and cold products that contain this ingredient are not permitted. Sales were moved “behind the counter” in the US (it is more widely available in other countries), with the requirement for the customer to produce photo identification and the requirement for the pharmacy to maintain a log of all sales, tracked by customer name and address. Not surprisingly, this put a damper on sales.

When pseudoephedrine was moved behind the counter, manufacturers of cough and cold products either had to accept a much smaller market for their pseudoephedrine-containing product, or reformulate.

Some companies reformulated their products to contain phenylephrine instead, which was the last remaining non-prescription ingredient that the FDA permitted for use to treat congestion. Phenylephrine is from a category of drugs called alpha-1 agonists: they stimulate alpha-1 receptors that are present throughout the body, including the nasal passages. It is used as a nasal spray, but more commonly in the United States as a oral product taken to treat nasal congestion. There was a problem with FDA’s historical approval, however. There was little convincing evidence phenylephrine, when taken orally, was actually effective at reducing congestion.

The case against phenylephrine

Phenylephrine is a poorly-absorbed drug (i.e., it has low bioavailability). Most of the drug is broken down during the absorption process, after passing through the liver. So there have been persistent questions if the drug was actually effective.

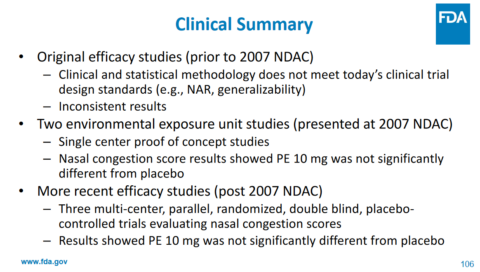

In clinical trials, oral phenylephrine was compared to other decongestants in a randomized controlled trial of 20 patients (way back in 1971) and found to be no more effective than placebo in reducing lung airway resistance. Another trial compared single doses of four different decongestants against placebo in 88 patients with congestion. It also found that phenylephrine was no more effective than placebo. In a review of the data that the FDA had considered, that review noted that for the 10mg dose, 4 studies showed efficacy and seven showed no difference from placebo. The authors concluded that a systematic review did not support the FDA’s decision. Other trials conducted since that time (like this one in 2009) are supportive of the conclusion that the 10mg dose is ineffective.

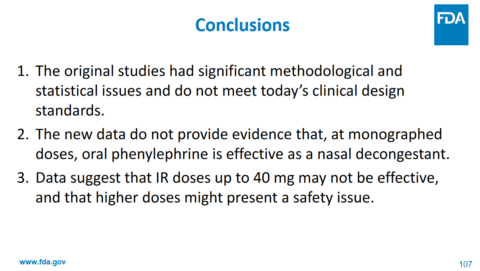

The fact that we are relying on trials conducted in the 1970’s pretty much tells us what we need to know about phenylephrine. Given how poorly it is absorbed, there is the question of whether simply giving bigger doses will work – and it turns out it may. However, the 10mg dose is what’s available in US cough and cold products – and the best evidence shows that this drug is effectively a placebo at that dose. I will point out that the manufacturers of the consumer products that contain this ingredient continue to write their own papers suggesting that there is evidence of efficacy. However, despite the large sales of these products, they have not produced any new randomized controlled trials to show that they are effective.

The FDA’s re-review of the evidence

In March 2023 I blogged about how the FDA had committed to re-review the evidence for phenylephrine. The Non-Prescription Drug Advisory Committee met in September 2023. The committee concluded that the evidence does not support that phenylephrine is effective as a nasal decongestant. Here are a few of the key slides and conclusions from that review:

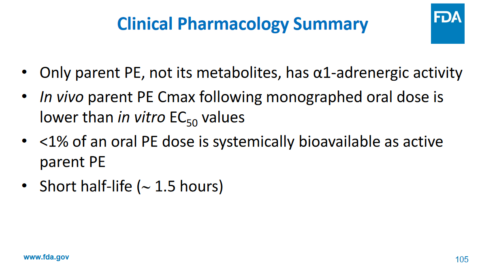

Phenylephrine has action against alpha receptors – not its metabolites. Less than 1% of the drug is actually absorbed as the “active” drug. The maximum effective blood concentration (Cmax) is lower than the EC50, which is half maximal effective concentration. Finally, the drug is quickly eliminated from the body. All of this suggests that the drug will not be clinically effective. And here is their bottom line on the clinical data, which won’t be surprising based on the pharmacology of the drug in the body:

The agency commented that the data available today refutes some of the assumptions made back in the 1970’s (pg. 55):

Finally, the science has changed in the interim, and a full understanding of the clinical pharmacology of PE [phenylephrine] when administered orally was not appreciated at the time that the Panel issued its recommendations. We now know that in addition to PE having less than 1% systemic bioavailability, the half-life is also significantly shorter than the original 4-hour dosing interval. These data were not available to the Panel, nor was the technology to fully assess oral bioavailability available until around the turn of this century. Therefore, is it not surprising that the Panel considered the equivocal findings in the original studies as sufficient to support a finding of efficacy (and safety) of PE 10 mg administered orally every 4 hours.

and, interestingly (pg. 60),

After careful review, we note that there were many methodological and statistical issues with these studies. We believe that these issues significantly limit any judgement of a statistical “win”, and more importantly a clinical “win”, for any of these studies. In fact, if these studies were submitted to the Agency today all would at most be considered Phase 1 studies at best. As a result, we believe that these studies do not stand up to the new data that are now available with regard to the efficacy of orally administered PE as a nasal decongestant.

Ultimately, the committee unanimously concluded that the evidence does not support that the recommended dosage of orally administered phenylephrine is effective as a nasal decongestant. Importantly, no safety issues with use of oral phenylephrine at the recommended dose were identified.

Your chance to comment

The FDA is currently inviting comments on this proposed order. Options available to the FDA include a final order removing oral phenylephrine from the “OTC monograph” which means that cough and cold products would no longer be permitted to contain oral phenylephrine. The FDA says it would provide manufacturers with time to come up with new formulations, or remove these products from.

Does this restricts consumer choice? Yes, but only from being marketed products that do not work as labelled. Having oral phenylephrine available with the FDA’s apparent approval, when it’s ineffective, offers a false choice that preys on consumer ignorance. And a regulatory standard that ensures approved product are both safe and effective is ultimately a win for consumers. While overdue, it’s to the FDA’s credit that it is willing to scrutinize, reflect, and act on the evidence, even for a decision with a large, but positive, consumer impact.